AFIR 3 features

-

Feature 1 Fully automated reaction path exploration

AFIR explores coordinate space by systematically inducing different transformations in a given system. Pathways for all types of reactions, including rearrangements of covalent and non-covalent bonds, can be explored with sufficient coverage.

-

Feature 2 Easy integration of kinetic analysis and simulation

The Rate Constant Matrix Contraction (RCMC) method is available to accelerate on-the-fly forward and backward kinetic simulations of AFIR or to analyze reaction path networks obtained by AFIR.

-

Feature 3 Various options to narrow the search space

Various options are available to narrow the search space and drastically reduce exploration costs, such as multi-component AFIR, double-sphere AFIR, bond pattern option, path selection option, thermodynamics-based and population flux-based options, etc.

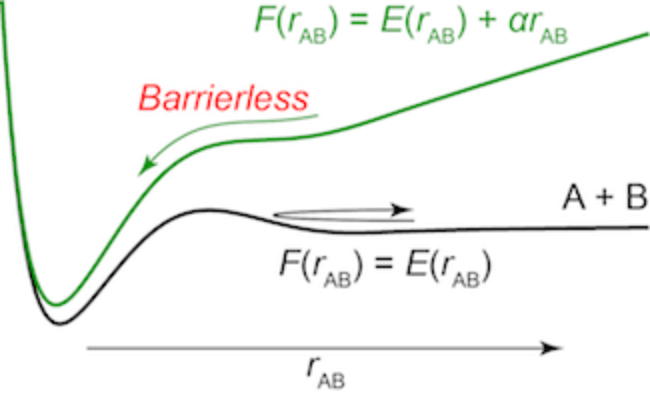

AFIR stands for "artificial force induced reaction." The idea of AFIR is simple; just push fragments A and B together or pull them apart. When both A and B are atoms, they can be pushed together by adding a linear function of their distance rAB to their potential energy E(rAB). In Figure 1, a diatomic potential curve E(rAB) is shown. This curve has a barrier which separates the reactant pair A + B and the product X. This barrier can be eliminated by adding the term αrAB to E(rAB), where α is a constant parameter. The resulting function, which is shown in blue in Figure 1, has no barrier. On this function, E(rAB) + αrAB, the product region, can be reached efficiently from the reactant pair just by minimizing the function.

Figure 1. A diatomic potential curve E(rAB) between atoms A and B (black curve) and the corresponding AFIR function E(rAB) + αrAB (blue curve). rAB is the distance between A and B, and α is a constant parameter.

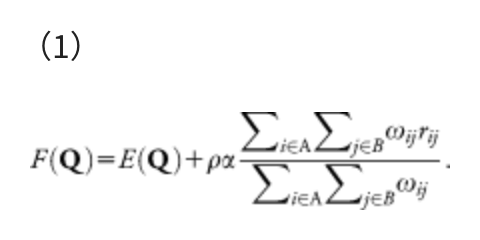

The same procedure can be done in polyatomic systems by minimizing the following AFIR function:

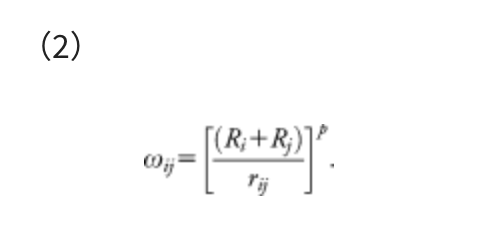

This function consists of two terms, i.e., the Born-Oppenheimer potential energy surface (PES) E(Q) of geometrical parameters Q and the artificial force term. The parameter α in the artificial force term determines the strength of the force. The coefficient ρ is either 1 to push fragments together, or −1 to pull them apart. The force term is given as a weighted sum of the distances rij between atom i in the fragment A and atom j in the fragment B, and the weight function ωij is:

This weight function assigns a stronger force to the closer atom pairs and a weaker force to the more distant pairs. In Eq. (2), the inverse distance 1/rij is scaled by Ri + Rj, the sum of covalent radii of atoms i and j, to treat all elements equivalently. It was confirmed that results did not strongly depend on the choice of p, and p is usually set to 6.0.

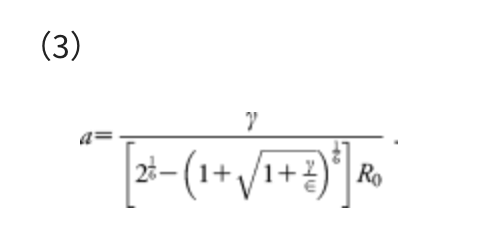

For convenience, the parameter α is determined by the following equation:

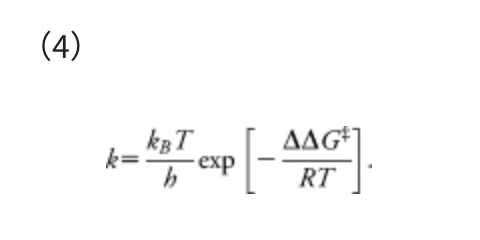

This α corresponds to the mean force that acts on two atoms in their direct collision on the Lennard–Jones (LJ) potential with collision energy γ, in the area from the minimum to the turning point. The standard Ar-Ar parameters of the LJ potential, i.e., R0 = 3.8164 Å and ε = 1.0061 kJ mol−1, were employed. The model collision energy parameter γ defines an approximate upper limit of the barrier height that can be eliminated by the force term. The γ parameter can be chosen by users, depending approximately on the highest TS energies searched. A choice of γ parameter may also be justified based on experimental conditions, such as temperature T, reaction time t, etc. In all examples we used here, the γ value was decided, assuming the rate constant k of the standard transition state theory:

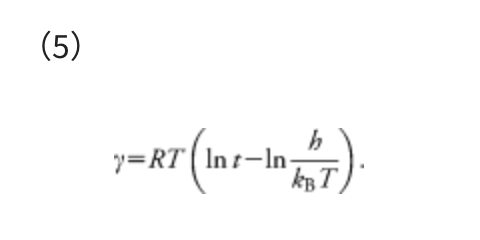

In Eq. (4), ΔΔG‡ is the overall Gibbs free energy of activation, kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature, h is the Planck constant, and R is the gas constant. The reaction time t can be estimated as the inverse of the rate constant, i.e., t ≈ 1/k. By substituting k = 1/t and taking inverse and natural logarithm of the both sides of Eq. (4), the γ required to overcome the barrier of ΔΔG‡ can be estimated as follows:

The temperature T assumed in each calculation is described in the corresponding section. One should set t to a larger value than those in actual reactions. This is because γ provides just an approximate upper limit of the barrier height. It is thus recommended to use a large value not to overlook important paths. Hence, t was set to 10 days in all the examples in this paper. For example, at T = 298.15 K, γ = 93.3 kJ mol−1 when t = 1 hour, γ = 101.2 kJ mol−1 when t = 1 day, and γ = 106.9 kJ mol−1 when t = 10 days. The γ value determined with t = 10 days is larger by ∼15% compared with the case t = 1 hour. Notably, a search with a very large γ gives many high barrier pathways that are not important in a given experimental condition, and such an exhaustive search requires very large computational costs.

For further details, see Chem. Rec., 2016, 16, 2232, J. Comput. Chem., 2018, 39, 233, or WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci., 2021, 11, e1538. (these papers are Open Access).